A Wood Duck Feathursday

The Wood Duck (Aix sponsa) is perhaps the most well known of the perching ducks in North America. This striking and highly-colorful waterfowl can be found in wooded swamps, ponds, marshes, and creeks in many parts of the U.S., southern Canada, and western Mexico. Most ducks are ground-nesters, but true to its name the Wood Duck nests in tree cavities, and unlike most other species of duck, the Wood Duck has sharp claws for perching in trees, which you can see in the detail of the bottom image.

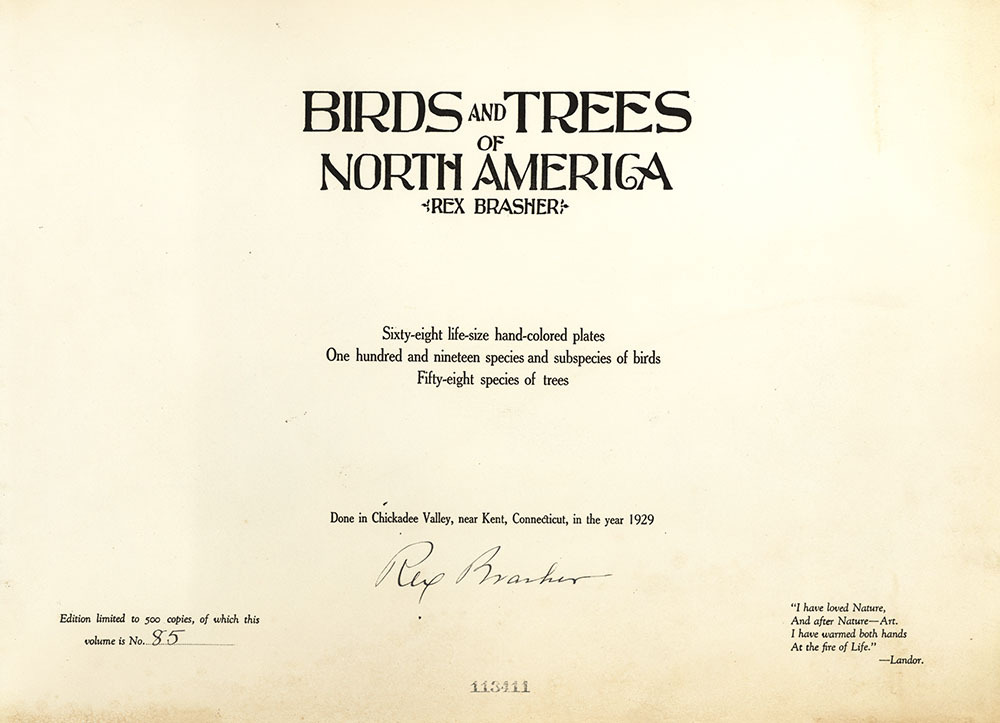

This plate, with details, is a hand-painted print from Rex Brasher’s massive, limited-edition, 12-volume set Birds and Trees of North America, self-published in Kent, Connecticut, between 1929 and 1932, containing thousands of hand-colored reproductions of Brasher’s paintings. In the late 19th century the Wood Duck was in serious decline, and by the early 20th century they were endangered in most of their former range. The Migratory Bird Treaty of 1916 and the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, however, helped to ensure the species’s gradual recovery. Brasher himself makes note of this in his own idiosyncratic way:

Let it be graven to our credit that these exquisite avian jewels have been given protection which insures their hold on the razor edge of life. Propagation and closed seasons in many states have resulted in increased numbers.

Find out more about Rex Brasher’s work, and/or view other posts from this set.

View more Feathursday posts.

FEATHURSDAY: Heron and Egret Social Distancing

Now, look how nicely these herons and egrets are maintaining distancing protocols. Clearly they care about each other’s health. If these wading birds can do it, so can we!

Herons and Egrets are not biologically distinct from each other, but I guess we like to think that they are, so we give them different names. Both are in the same family, Ardeidae, although those shown here fall into four genera, Egretta, Ardea, Nycticorax, or Nyctanassa. Click on the images to see who these folks are.

These images are hand-painted prints from Rex Brasher’s massive, limited-edition, 12-volume set Birds and Trees of North America, self-published in Kent, Connecticut, between 1929 and 1932, containing thousands of hand-colored reproductions of Brasher’s paintings. Brasher is not only known for his elegant bird illustrations, but also for his idiosyncratic observations about behavior and character. Of the Great Egret, he writes:

… black of heart, this is the most vicious and murderous of the Heron family. Untamable, fierce and bloodthirsty, they use their dagger bill with Moro accuracy on any living thing, Cats, dogs, birds, even human beings, are not safe within range of their piston stiletto.

Of the Great Blue Heron, he observes:

During courtship the fencing bouts between males are apparently savage affairs but in reality only regulation small-boy scraps – every thrust being parried with accurate skill. They are dignified even in fighting.

Find out more about Rex Brasher’s work, and/or view other posts from this set.

View more Feathursday posts.

And follow these herons’ example: keep your distance!

Feathursday Kestrels!

The American Kestrel (Falco sparverius), sometimes called a Sparrow Hawk after the unrelated Eurasian Sparrowhawk, is among our favorite neighborhood raptors. Around our university we find Owls, Cooper’s Hawks, Red-tailed Hawks, and Peregrine Falcons, but the Kestrel is the smallest (except for the Saw-Whet Owl) and most ubiquitous in our vicinity. They are quite colorful and have a regal but sweet bearing. Importantly, they are excellent at keeping the mice at bay, but they also hunt other small rodents, large insects (e.g., grasshoppers and dragonflies), and small birds. They also seem quite at home among human populations. Max once saw Kestrel swoop past his nose to snag a House Sparrow in mid-flight in a hail of scattered feathers.

The various subspecies of American Kestrel shown here are from hand-painted prints in Rex Brasher’s massive, limited-edition, 12-volume set Birds and Trees of North America, self-published in Kent, Connecticut, between 1929 and 1932, containing thousands of hand-colored reproductions of Brasher’s paintings. There are 17 recognized subspecies of the American Kestrel. Shown here, top to bottom, are the head of the San Lucas Kestrel (F. s. peninsularis), found in Baja California; a couple of F. s. sparverius, the subspecies found here and throughout the U.S., Canada, and Mexico; two so-called Desert Kestrels, a subspecies that is no longer recognized; a couple of San Lucas Kestrels along with a Little Kestrel (F. s. paulus) found from Louisiana to Florida; and the head of F. s. sparverius, the most common subspecies.

Find out more about Rex Brasher’s work, and/or view other posts from this set.

View more Feathursday posts.

Monday Motivation Owl

It was -7F earlier this morning in Milwaukee, with a wind-chill of -24F, but that doesn’t seem to bother these Northern Hawk Owls (Surnia ulula) much. Their coat of insulating feathers and little feathered booties keep them quite comfortable on a day like today. In fact, they seem to prefer a day such as this. Their motivation not only makes them hardy winter birds, but they are also one of the few owls that hunt only by day, rather than at night like typical owls.

Once again, this is a hand-painted print from Rex Brasher’s massive, limited-edition, 12-volume set Birds and Trees of North America, self-published in Kent, Connecticut, between 1929 and 1932, containing thousands of hand-colored reproductions of Brasher’s paintings. Brasher notes the Hawk Owl’s voracious feeding habits: “I encountered a congregation among the spruces of Sebago Lake, Maine, which were doing their utmost to exterminate the mice of the vicinity.” One specimen Brasher shot “had seven field mice in its stomach!” Truly motivated owls.

Find out more about Rex Brasher’s work, and/or view other posts from this set.

View more motivated (and some unmotivated) owls.

Feathursday Name That Psittacidae

We are still in a tropical frame of mind from last week, so this week we present these gregarious parrot-like birds, the only two species of Psittacidae that were endemic to the United States. The operative verb here is “were,” as one is believed to be extinct for the past 80 years, and the other, while still extant, has had its habitat reduced to the western mountain range of Mexico.Once again, these plates are hand-painted prints from Rex Brasher’s massive, limited-edition, 12-volume set Birds and Trees of North America, self-published in Kent, Connecticut, between 1929 and 1932, containing thousands of hand-colored reproductions of Brasher’s paintings.It is a great shame that we no longer find these colorful parrots in the American landscape. Still, do you think you could Name These Birds?Give it a try, and check back after 4:40 pm CST for the answer. Good luck!Find out more about Rex Brasher’s work, and/or view other posts from this set.View more Feathursday posts.

And the answer to this week’s #Feathurday Name That Bird challenge is … top, the Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis); bottom, the Thick-billed Parrot (Rhynchopsitta pachyrhyncha)!! The Carolina Parakeet was once quite prevalent in the eastern U.S., from Wisconsin to the Gulf, from New York to Florida, and from the Atlantic coast to eastern Colorado. But by the mid-19th century the species had become rare, and a was extremely rare by the time Brasher described it, finally being declared extinct in 1939. Writing in the late 1920s, Brasher observed that “In 1896 I saw five flying over the Everglades near the headwaters of the Miami River … . A few still may exist in extreme southern Florida.”

The Thick-billed Parrot once ranged into southern New Mexico and Arizona, and possibly as far north as Colorado. But because of hunting, logging, habitat reduction, the current population has been reduced to only a couple of thousand restricted to the Sierra Madre Occidental of western Mexico.

Congratulations again to @itsashamepeoplesuck for identifying both species correctly. They also pointed out that the bird in the background of the bottom plate may be a Green Parakeet (Psittacara holochlorus), rather than a female Thick-billed, and we think they may be right. The sexes of the Thick-billed have similar coloration, yet the bird depicted here has no red markings and a different colored beak, looking very much like a Green Parakeet. Good call, @itsashamepeoplesuck! Once again you get bonus points and bragging rights!

Thanks for playing Name That Bird!!

Feathursday Name That Psittacidae

We are still in a tropical frame of mind from last week, so this week we present these gregarious parrot-like birds, the only two species of Psittacidae that were endemic to the United States. The operative verb here is “were,” as one is believed to be extinct for the past 80 years, and the other, while still extant, has had its habitat reduced to the western mountain range of Mexico.

Once again, these plates are hand-painted prints from Rex Brasher’s massive, limited-edition, 12-volume set Birds and Trees of North America, self-published in Kent, Connecticut, between 1929 and 1932, containing thousands of hand-colored reproductions of Brasher’s paintings.

It is a great shame that we no longer find these colorful parrots in the American landscape. Still, do you think you could Name These Birds?

Give it a try, and check back after 4:40 pm CST for the answer. Good luck!

Find out more about Rex Brasher’s work, and/or view other posts from this set.

View more Feathursday posts.

Feathursday Name That Bird

After being snowbound in Milwaukee for a few weeks, the mind inevitably turns to the tropics. Hence, our choice for this week’s #Feathursday Name That Bird puzzler. This colorful couple spend most of their days in sunny Guatemala and Mexico, but they regularly venture north and are not uncommon in the Gila River valley of Arizona and New Mexico, and occasionally into the southernmost portion of southwest Texas.This is yet another hand-painted print from Rex Brasher’s massive, limited-edition, 12-volume set Birds and Trees of North America, self-published in Kent, Connecticut, between 1929 and 1932, containing thousands of hand-colored reproductions of Brasher’s paintings. Of the genus, or general group these birds belong to, Brasher writes:In the deep tropical forests of Central and South America are found over thirty species of this family. Magnificently colored with iridescent sheen, only Hummingbirds approach the splendor of the males’ apparel… . Altho [sic] arboreal the feet are week and [members of this genus] seldom move on tree limbs. Disinclination to walking is so strong that rather than travel a foot or two along a branch to seize a fruit, they prefer using their wings. They are expert flycatchers, pursuing insects with spectacular acrobatic swoops, sideslips and even turning somersaults in the chase.So, let’s get into a warmer frame of mind and see if you can NAME THAT BIRD! 10 points if you name the genus, and another 15 points and bragging rights if you name the specific species.We’ll post the answers after 4 pm CST. Good luck!Find out more about Rex Brasher’s work, and/or view other posts from this set.View more Feathursday posts.

My Goodness! We were so busy toward the end of the day yesterday, we just couldn’t get our answer to this week’s #Feathursday Name That Bird puzzler out on time. Apologies to all those who have been sitting around biting their nails in anticipation.

And the answer is … the Elegant Trogon (Trogon elegans)!! And this image is specifically of the “coppery-tailed” subspecies (Trogon elegans ambiguus).

Congratulations once again to @itsashamepeoplesuck for identifying the genus correctly as Trogon for 10 points. For the extra 15 points and bragging rights, they also guessed the Mountain Trogon (Trogon mexicanus), which looks extremely similar. So much, so, that @itsashamepeoplesuck believes Brasher got it wrong. The evidence they presented is pretty compelling, but we’re not able to parse it out, so we grant @itsashamepeoplesuck the extra 15 points for a whopping total of 25 points for their tenacity and investigative prowess!

We are such bird nerds!

We hope to see you next week for another round of NAME THAT BIRD!

Feathursday Name That Bird

After being snowbound in Milwaukee for a few weeks, the mind inevitably turns to the tropics. Hence, our choice for this week’s #Feathursday Name That Bird puzzler. This colorful couple spend most of their days in sunny Guatemala and Mexico, but they regularly venture north and are not uncommon in the Gila River valley of Arizona and New Mexico, and occasionally into the southernmost portion of southwest Texas.

This is yet another hand-painted print from Rex Brasher’s massive, limited-edition, 12-volume set Birds and Trees of North America, self-published in Kent, Connecticut, between 1929 and 1932, containing thousands of hand-colored reproductions of Brasher’s paintings. Of the genus, or general group these birds belong to, Brasher writes:

In the deep tropical forests of Central and South America are found over thirty species of this family. Magnificently colored with iridescent sheen, only Hummingbirds approach the splendor of the males’ apparel… . Altho [sic] arboreal the feet are weak and [members of this genus] seldom move on tree limbs. Disinclination to walking is so strong that rather than travel a foot or two along a branch to seize a fruit, they prefer using their wings. They are expert flycatchers, pursuing insects with spectacular acrobatic swoops, sideslips and even turning somersaults in the chase.

So, let’s get into a warmer frame of mind and see if you can NAME THAT BIRD! 10 points if you name the genus, and another 15 points and bragging rights if you name the specific species.

We’ll post the answers after 4 pm CST. Good luck!

Find out more about Rex Brasher’s work, and/or view other posts from this set.

View more Feathursday posts.

Name That Bird Feathursday

The temperature has dropped here in the Upper Midwest, and we’ve had three days of snowfall, but that probably wouldn’t bother these arctic-loving birds one bit. There are three species in this genus, and all are shown here. Two of them breed right on the shores of North America’s Arctic Ocean, but all three can be found either in the Upper Midwest, on the Great Plains, or both during non-breeding season. Guess the common name for the genus and you get 10 points. But then try to name each species for 5 points a piece for a total bird-nerd-bragging-rights grand prize of 25 points!These little guys are from Rex Brasher’s massive, limited-edition, 12-volume set Birds and Trees of North America, self-published in Kent, Connecticut, between 1929 and 1932, and containing thousands of hand-colored reproductions of Brasher’s paintings. But, maybe we were wrong that our snowy weather wouldn’t bother these feathered folk. Brasher observes that:One of Nature’s malignant forces, in the form of blizzard, sometimes engulfs [this genus]. They seem to lose direction sense and then themselves, for thousands have been found dead from striking the ground. Blinding snow gave no chance to see where they were going and they flew full speed downward.Yikes!So, plug in your bird brains, and see if you can NAME THESE BIRDS!We’ll post the answers after 4 pm CST. Good luck!Find out more about Rex Brasher’s work, and/or view other posts from this set.View more Feathursday posts.

Here are the answers to this week’s #Feathursday Name That Bird puzzler:

The common name for the genus is Longspur; scientific name, Calcarius. The three species of Longspur shown here from top to bottom are:

Lapland Longspur (Calcarius lapponicus).

Clockwise: adult male, spring; adult male, winter; adult female.

Smith’s Longspur (Calcarius pictus).

Clockwise: adult male, spring; adult male, autumn; adult female.

Chestnut-collared Longspur (Calcarius ornatus).

Clockwise: adult male, spring; adult female; adult male, winter.

Clockwise: adult male, spring; adult male, winter; adult female.

Smith’s Longspur (Calcarius pictus).

Clockwise: adult male, spring; adult male, autumn; adult female.

Chestnut-collared Longspur (Calcarius ornatus).

Clockwise: adult male, spring; adult female; adult male, winter.

The identifying giveaway is also embedded in the common and Latin names: their elongated hind claws.

We have TWO 25-point, bird-nerd-bragging-rights grand prize winners this week: @leftfootism and @itsashamepeoplesuck!! Well done and congratulations!! We definitely want these folks around on our next birding adventure.

See you next week for another go at NAME THAT BIRD!

Name That Bird Feathursday

The temperature has dropped here in the Upper Midwest, and we’ve had three days of snowfall, but that probably wouldn’t bother these arctic-loving birds one bit. There are three species in this genus, and all are shown here. Two of them breed right on the shores of North America’s Arctic Ocean, but all three can be found either in the Upper Midwest, on the Great Plains, or both during non-breeding season. Guess the common name for the genus and you get 10 points. But then try to name each species for 5 points a piece for a total bird-nerd-bragging-rights grand prize of 25 points!

These little guys are from Rex Brasher’s massive, limited-edition, 12-volume set Birds and Trees of North America, self-published in Kent, Connecticut, between 1929 and 1932, and containing thousands of hand-colored reproductions of Brasher’s paintings. But, maybe we were wrong that our snowy weather wouldn’t bother these feathered folk. Brasher observes that:

One of Nature’s malignant forces, in the form of blizzard, sometimes engulfs [this genus]. They seem to lose direction sense and then themselves, for thousands have been found dead from striking the ground. Blinding snow gave no chance to see where they were going and they flew full speed downward.

Yikes!

So, plug in your bird brains, and see if you can NAME THESE BIRDS!

We’ll post the answers after 4 pm CST. Good luck!

View more Feathursday posts.

No comments:

Post a Comment